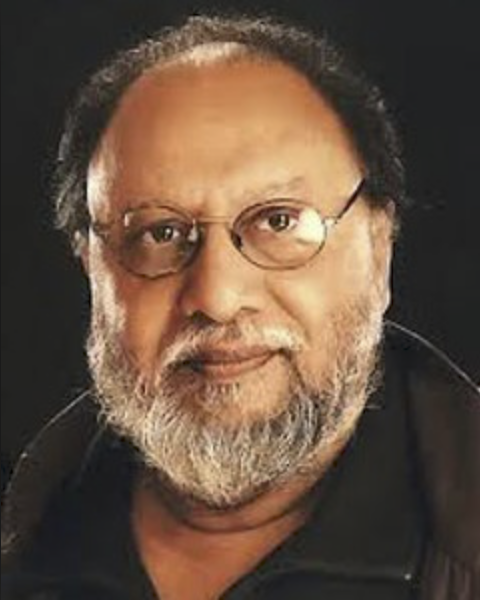

Within India, by far the best-known critic of modern science is the sociologist Ashis Nandy. Nandy worries that science ‘is threatening to take over all of human life, including every insterstice of culture and every form of individuality’. He believes that scientists are amoral and opportunistic, prone to claim credit for the good done in the name of science, while hastily repudiating the evil. They try to ‘sell the idea that while each technological achievement marked the success of modern science, each technological perversity was the responsibility of either the technologist or his political and economic mentors, not that of the scientist’. At one place, he goes so far as to write that ‘science is the basic model of domination in our times and the ultimate justification for all institutionalized violence’.Notably, in his own attacks on modern science Ashis Nandy invokes the support of Mahatma Gandhi. Nandy claims that ‘Gandhi rejected the modern West primarily because of its secular scientific worldview’. He further writes that ‘Gandhi’s rejection of modern science is by far the best known theme in his attack on the West’.

“The first generation of modern scientists in India had two possible techniques of coping with the feelings of national inferiority induced by their participation in the world of modern science. The first was to separate the culture and the content of science and, then, fight either for a plural culture of science which would accommodate the Indian worldview or for the substitution of the dominant culture of science by a new culture more congruent with Indian values. Neither was truly practicable at a time when the difference between science and the culture of science was not that obvious. The first generation of Indian scientists, therefore, opted for a third technique. Most of them spent their professional careers trying to build an entirely new Indian structure of science. Some gave up the task half way, finding it too onerous; they preferred to become political activists, institution-builders, or academic bureaucrats and gave up science, if not formally, at least de facto . Others, a much smaller group, preferred to go the whole hog and fought a losing battle against the formidable edifice of modern science. Both responses were consistent with the logic of a colonial situation, and one must judge for oneself which was the more tragic dead end. “